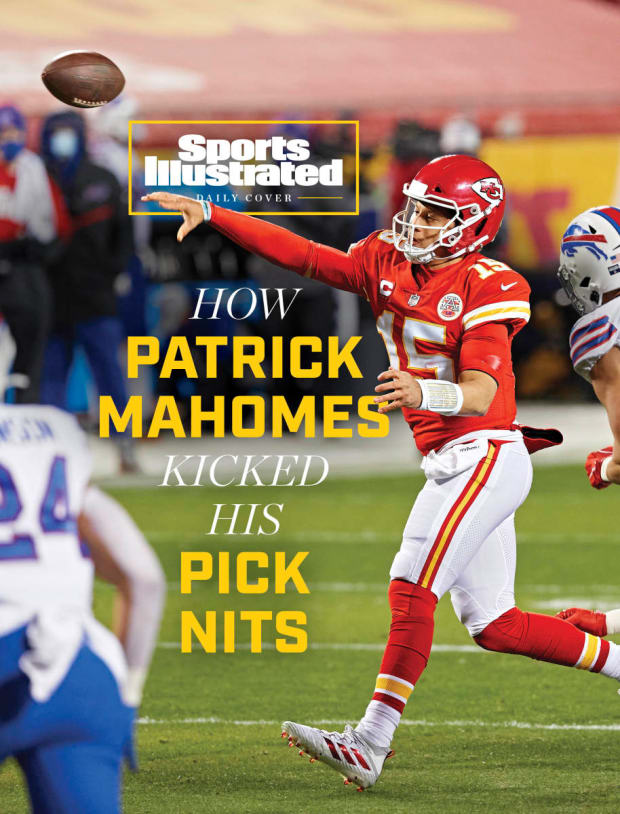

Two years after being named MVP, the Chiefs' QB went and halved his INT rate. Turns out his physical skills were obscuring his genius.

The University of the Incarnate Word postponed its 2020 football season until the spring, but the team kept practicing last fall. Sometimes coach Eric Morris would move the Sunday practice time, and his assistant coaches at the San Antonio school would laugh, knowing exactly why he’d done it. He wanted to watch the player who appears, at times, to be a deity incarnate.

Morris was Patrick Mahomes’s offensive coordinator at Texas Tech. When Morris watches Mahomes now, he does not just see the best player in the NFL, like the rest of us do. He sees the previous versions of Mahomes and the progress that Mahomes has made, even since becoming an NFL star.

In 2018, his first season as the Chiefs’ starter, Mahomes won the league’s MVP award. He put up such outrageous numbers—50 touchdown passes, 5,097 yards—that it was natural to wonder whether he could keep playing that well.

He has not. He has played better.

In that MVP year, Mahomes threw 12 regular-season interceptions in 580 attempts. In the past two season, including the playoffs, he has thrown 13 picks in 1,324 tries. He has cut that MVP-year interception rate in half. (His 1.0 interception percentage these past two seasons rivals the best stretch of Tom Brady’s career.) His completion percentage is basically the same. His yards per attempt have declined slightly, but by taking better care of the ball—he is also fumbling less often—Mahomes has made Kansas City’s best-in-the-league offense even more efficient. In 2018, the Chiefs averaged 14.7 passing first downs per game, fourth in the NFL. This year, they averaged 16.1, first by a significant margin.

“He’s done a better job of taking what the defense gives him,” says Morris. “He’s really matured in being able to know that these five- and six-yard gains on a simple little hitch are all a part of moving the chains and getting first downs.”

Mahomes wowed scouts with his arm in college, but there were questions back then about whether he could adapt his game from the relatively simple Air Raid offense to the NFL. Morris says that when Mahomes played for Texas Tech, “our center called all our protections for us in our scheme.” Some feared that the Air Raid was hiding Mahomes’s flaws. Looking back, it hid his genius.

Morris says that when Mahomes threw an interception in college, the quarterback did not need to ask his coaches what he did wrong. He knew.

“He’d watch [the replay] the night of the game, and by the time you get to film review he’s basically answering questions for you: I know coach, they rolled Cover-3 and… .”

Mahomes’s progression can be measured in many ways, but maybe the easiest is his interception percentage:

- Sophomore year at Texas Tech: 2.6%

- Junior year at Texas Tech: 1.7%

- First year as an NFL starter: 2.1%

- Last two years as an NFL starter: 1.0%

In Lubbock, Mahomes looked like the ultimate backyard quarterback, slinging it whenever he thought he could get away with it. It was hard to envision him playing so impeccably unless you were with him every day. Morris saw what opposing NFL coaches have learned about Mahomes: “He seemed to never make the same mistake twice.”

Mahomes threw six interceptions this season. But even that statistic undersells how smart he is. Watch the video and you see somebody so smart, so good at organizing the chaos surrounding him, that he rarely makes a significant mental mistake.

He didn’t throw his first interception of 2020 until his fifth game, in Las Vegas. Mahomes forced a ball deep to Travis Kelce in triple coverage, but this was one of those weird and rare situations where there existed worse choices than throwing into traffic. It was fourth-and-seven. The Chiefs trailed the Raiders by nine with fewer than six minutes remaining. As Mahomes surveyed the field, he didn’t have any good options. He knew he couldn’t take a sack. He knew it was pointless to complete a pass well short of the line of scrimmage, to a player who was sure to get tackled.

Mahomes didn’t throw another interception until his 10th game, also against the Raiders, and this one wasn’t his fault: Receiver DeMarcus Robinson failed to come back to the ball. (ESPN’s Dan Orlovsky explains here why he blames Robinson.) By the time Mahomes took the field in Miami on Dec. 13, Kansas City was 11–1. He had thrown just those two interceptions.

He would throw three picks against the Dolphins, but none were of the What the f--- were you thinking? variety. The first was just confirmation of how many moving parts there are on a given play. Miami’s Andrew Van Ginkel was lying face-down on the ground in front of an open Kelce. Mahomes fired an accurate pass to his tight end, only to watch the opposing linebacker spring to his feet and tip the ball over Kelce’s head, to Miami cornerback Byron Jones.

Mahomes’s next two picks that afternoon were failures of execution. He sailed high a pass intended for Clyde Edwards-Helaire. He also threw a little short to Tyreek Hill, and Xavien Howard, one of the best corners in the league, made a spectacular one-handed interception—but by that point in the fourth quarter the Chiefs led 30–10.

Afterward, the quarterback admitted that he got “angry,” at least in the moment, about throwing three interceptions, but he seemed to sense there was a mystical quality to them. He threw eight picks in the calendar year 2020, and five of them came in Miami’s Hard Rock Stadium: two in Super Bowl LIV against the 49ers and three against the Dolphins. The Chiefs won both games anyway.

Besides, Mahomes didn’t stay angry for long: He threw three TDs and no INTs in the Chiefs’ win the next week over the Saints. It wasn’t until Kansas City’s 15th game, against the Falcons, that the QB made an obvious and significant mental mistake that led to an interception. Mahomes did not see Atlanta linebacker Foyesade Oluokun in front of Kelce. Oluokon picked off Mahomes. It was Mahomes’s 572nd pass of the year.

Mahomes threw four interceptions in a college game once, against Oklahoma during his sophomore year. Texas Tech lost 63–27. This was the kind of performance that can make pro scouts nervous: Against faster players, Mahomes looked like he got exposed.

His old offensive coordinator saw it a different way. Morris says, “He probably kind of pressed for the first time on the road when we did get down,” but he also points out that, though nobody wanted to say it, everybody understood Oklahoma had a lot more talent than Texas Tech. The Sooners’ offense, led by future Heisman winner Baker Mayfield, was explosive, and Mahomes tried to match that by himself. Morris says, “I remember the first one was a Go ball in the end zone. Our receiver has got to make a play on it. … Those were games where you know, with Oklahoma’s efficiency, you pretty much have to score every single time.”

The Mahomes we see today is surrounded by as much offensive talent as any quarterback in the league. When he faces Tom Brady on Sunday, it will be a matchup of two of the best quarterbacks of all time. Mahomes and Brady are very different: Mahomes throws no-look passes and easily dashes for first downs, while Brady is the best version of a classic pocket passer in history. But their journeys are quite similar.

Both played baseball well enough to be drafted in the majors but gave that up because of a stronger passion for football. Both experienced some college struggles—Brady to secure a starting job, Mahomes to win games—that helped forge their fortitude. Both were drafted later than they should have been (though, obviously, Brady’s falling to pick No. 199 is a lot different than Mahomes’s falling to No. 10) but landed with exactly the right coach for their talent.

And both Mahomes and Brady have a mental aptitude for the game that is easier to see in the NFL than it was in college. Brady got better as football became more complicated because his ability to process and execute in real time is extraordinary. Scouts who focused on his apparent physical limitations at Michigan missed out on how quickly he thinks. Mahomes was overlooked for a reason that is both similar and the opposite: Scouts were so enamored of his physical gifts that they missed out on how quickly he thinks. It was easy to see him as a guy who got by on arm talent alone.

Morris is both amazed and unsurprised by how great of a pro Mahomes has been. The coordinator was there when the roots took hold.

Mahomes is “wise beyond his years in decision-making,” Morris says. “ ‘I can’t take this chance. It’s not worth it to throw an interception.’ ”

Chiefs teammates marvel, too, at Mahomes’s spatial awareness. When he errs, he knows how and why before he walks off the field, and he applies it to the next play. Anybody watching the QB at Texas Tech could have seen that he had the physical tools to play in the NFL, but his mental gifts were partially hidden by the Air Raid and his sometimes overmatched teammates.

When the Chiefs’ staff visited Lubbock to meet with Mahomes before the 2017 draft, the QB was asked to break down Kansas City’s offense on a whiteboard. When he finished, coach Andy Reid told the Texas Tech staff, “Wow, that’s one of the best board sessions I’ve ever been a part of.” If Reid was surprised, the Tech staff was not. And now, four years later, neither are we.

The last time Mahomes played in a Super Bowl, he had two interceptions. One was a forced throw, deep on third-and-12, that effectively served as a short punt. The other was a failure of execution—he had Hill open but threw behind him. Mahomes has no doubt learned from both mistakes. After all, Patrick Mahomes never seems to make the same mistake twice.

0 Comments