There’s no telling what you’ll get on any given snap, but two months into the season he is the reason the Bills are 7-2 and thinking about football in February.

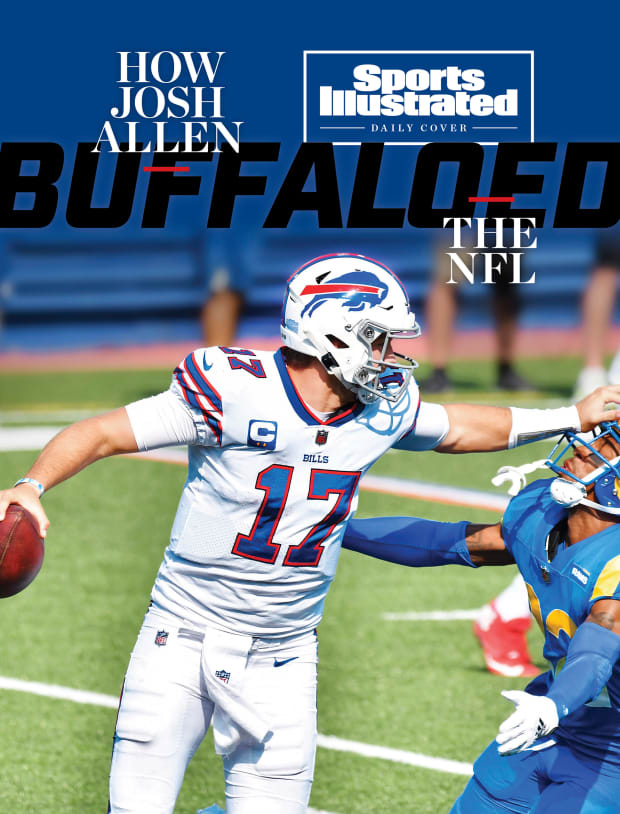

The confusion starts at the snap, allowing the pass rusher firing off the right edge the clearest advantage in football: an uninhibited shot at the quarterback. The quarterback spins to escape, only the pass rusher isn’t shaken. So the quarterback backpedals, furiously, like he’s moonwalking on fast forward. Meanwhile, from the opposite side, another defender closes in. As the quarterback shuffles frantically, he moves the ball from his throwing hand to his left, and, with his right hand free, reaches toward the first pass-rusher. The moment his stiff-arm connects, something remarkable happens: The quarterback is now the aggressor.

In one motion, he snatches the defender’s facemask and drags him into the path of his oncoming teammate. Once both defenders go to the ground, the quarterback stumbles backward and switches the ball back to his right hand, but just as he does the best defensive player on the planet arrives. Aaron Donald raises both arms as he closes in for a sack, but instead the quarterback puts out another straight arm and uses Donald’s own freight-train momentum to relegate him to innocent bystander status.

The snap, coming while trailing with 49 seconds left, was at the opponent’s 15-yard line—now the quarterback is 19 yards behind the line of scrimmage. Finally, with nearly a half-ton of pass rusher left in his wake, he backpedals once more, toward the sideline, and flicks the ball out of the end zone, 45 yards downfield. There is a flag—for the face-mask grab on the defender turned human shield—but for now the clock is stopped, and disaster is averted.

If one play embodies the chaotic, poetic, and befuddling nature of the Josh Allen Experience, perhaps it was that beautiful facemask penalty, on which the quarterback was less Joe Cool and more Chuck Norris. “It looked like a bar fight,” Bills general manager Brandon Beane says. “Like he was being jumped, and he’s got one hand tied behind his back. When [dude] gets close, he goes, I’m going to sling him. And he rag-dolled him!” Which is to say, Josh Allen did something unlike anything anyone in football has seen. Again.

It seems the Bills, who once led this game 28–3, are likely doomed as they line up for a second-and-25 at the Rams’ 30-yard line. No matter. Four plays later, Allen is celebrating his game-winning touchdown pass.

The infinite possibilities of Josh Allen reveal themselves not game by game or even play by play, but rather second by can’t-look-away second. Impossible feats beget improbable outcomes, and potential disaster always looms nearby. Teammates who know the QB for the magic tricks—yes, actual magic tricks—he performs in the locker room find him Houdini-adjacent on the field, too. His size and skill set combo defies the conventional wisdom applied to professional quarterbacks (as well as the now-buried notion that Buffalo’s ascending QB doesn’t belong in the NFL). None of which is to suggest that Allen is perfect or mistake-free or even smooth. It just means: There might not be another NFL player who brings the same edge-of-your-seat terror to every single play. “It’s like, oh, you think I’m throwing it?” says Dion Dawkins, the tackle who protects Allen’s blindside. “Well, here’s a stiff-arm!”

The phrase Josh Allen Experience has been deployed as an insult in years past, in part because the good, the bad and the holy s--- often take place simultaneously. Going to Allen after the last might-have-been-franchise quarterback in Buffalo, conservative veteran Tyrod Taylor, was like waving goodbye to the kiddie roller coaster and hopping on the screamer that barely passes its daily safety inspections. If the last generation of great passers was typified by world-class surgeons—Tom Brady, Peyton Manning, Drew Brees—diagnosing defenses and dissecting them with painstaking precision, Allen arrives in the operating room with a bowhunting knife and a bottle of Wild Turkey from which he takes generous slugs. Even the NFL’s best improvisers—Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson and Russell Wilson—work through a flow chart on any given play. Allen’s options, though, can seem wider, perhaps infinite. Allen represents an outlier among outliers.

One play before that second-down bar brawl broke out, he had an opportunity to scramble for about five yards but, instead, at the last moment, tried to flick a lateral to an unsuspecting teammate, the ball skipping out of bounds. Unsuspecting because, well, who does that? Josh Allen does that. The play, which was ruled an incomplete pass, was reminiscent of the attempted lateral Allen flipped while getting dragged down at the end of a long run late in the Bills’ comeback in Houston last January.

He is rarely described as poetic, like Mahomes; isn’t naturally smooth, like Jackson. Instead, he recalls a famous Mike Tyson quote—“My style is impetuous, my defense is impregnable”—in that he doesn’t exactly make sense until he does.

And yet, this glorious, zany, cover-your-children’s-eyes experience is … working? The Bills look formidable, so good that this team reminds Buffalo legend Thurman Thomas of the Super Bowl squads he played on, the ones that dropped four-straight heartbreakers. For the first time in forever, the best quarterback in the AFC East isn’t Tom Brady and doesn’t play for New England. Allen—Josh Allen—is the reason the Bills are sitting at 7-2, and Western New York is considering the prospect of February football.

So how in the name of chaos theory did Allen and the Bills end up here? How did Allen and his comebacks make him the NFL’s foremost nut-cruncher—his term—and send long-ago-cursed Buffalo fans scurrying to buy another ticket for the wildest ride in football? Like every snap he takes, the route was, shall we say, more interesting than that of a typical quarterback.

* * *

When Beane took over the Bills in 2017, he inherited both the longest playoff drought in professional sports—18 seasons—and a quarterback carousel that never seemed to stop spinning. It was no surprise then that he took a particular interest in the ’18 QB class, which featured two Heisman winners in Oklahoma’s Baker Mayfield and Louisville’s Lamar Jackson; USC’s Sam Darnold, who was the presumed front-runner to be drafted No. 1 for most of that college season; and UCLA’s Josh Rosen, considered a blue-chip prospect since his high school days. Then there was Allen, the Wyoming flamethrower with the forgettable stat line, a non-recruit so distanced from the prep QB circuit that he might have thought Elite 11 was an Oceans franchise spin-off.

But the more Beane watched Allen, the more he saw specific ways that Allen’s college experience would translate favorably to Buffalo. With several games each season featuring winds gusting at 15 miles an hour or more, Bills quarterbacks required big-boy arm strength. That, and comfort in snow. And the ability to deal with adverse conditions—and the talent around Allen at Wyoming his senior season qualified as such. “There was really no one Josh was playing with where you said, This kid is going to have a chance in the NFL,” Beane says.

The GM and his Bills contingent flew that spring to Wyoming’s campus in Laramie, beginning the car-wash process for all their top prospects. Allen’s workout put Beane at ease. “Just needed more coaching,” he says.

Buffalo held the 12th pick, and Beane knew that the QB-needy Browns, who held the No. 1 and No. 4 selections, would take Mayfield at the top of the draft. But he wasn’t sure what Dave Gettleman, the Giants’ new general manager, had in mind at No. 2 (Eli Manning was still the de facto starter). And on the day the Bills worked out Allen, news broke that the similarly QB-deficient Jets had traded up with the Colts to No. 3, ostensibly for a quarterback.

To Beane, Allen represented the draft class’s unmolded clay. He brought the highest risk, sure. But also, potentially, the highest reward. Beane saw a talent so raw that he figured—hoped—other teams might be scared away.

Beane waved away the obvious concerns. He liked that Allen hadn’t taken the typical route to the NFL scrutiny. That he’d grown up on a 3,000-acre cotton farm in Firebaugh, Calif., near Fresno, and proudly joined the Future Farmers of America. That he played multiple sports in high school, wasn’t coddled on the showcase camp circuit and started his college years at Reedley, a juco where the husband of one family cousin happened to be an assistant coach. Wyoming’s coaches stumbled upon the QB only while recruiting someone else. “I thought he had the potential to be a Division-I guy,” says Ernie Rodriguez, his offensive coordinator there.

In Allen’s first year after transferring, he broke his collarbone on a reckless run where he failed to slide. In his second, he played some of his worst football against Nebraska, Iowa and Oregon.

At that point he presented evaluators a different type of experience, but Beane saw the clay, the ability to build a passer from scratch. He loved Allen’s endless potential, his all-weather fit and his unassuming personality in a city where the biggest celebrity might be the wings. Allen was relatable, quoting from Will Ferrell movies and growing out a glorious mustache and cracking dad jokes. “No. 1 or 2 most likable guy I’ve been around,” says Jordan Palmer, who would eventually become Allen’s private quarterback coach. “Just a magnet.”

Beane was active on draft night, studying the first 11 picks in search for where he might be able to trade up. (The draft-day

revelation of racially insensitive tweets from his high school days, for which Allen apologized in media appearances that day, did not affect his draft stock.) Beane tried to move to No. 4, the Browns’ second pick. When that failed, he agreed to a deal that would have sent two first-rounders to the Broncos for their choice at 5, with one caveat: The swap would be off if N.C. State pass rusher Bradley Chubb was still on the board. When Chubb slid, Denver kept the pick. Finally, Beane worked out a deal with the Bucs, giving up his No. 12 and two second-rounders to move up five slots. At Buffalo’s facility in Orchard Park, the GM headed downstairs to the media room, all fired up. “The looks on some of their faces, I’ll never forget it,” says Beane. “It was like I had just screwed everything up.”“Listen,” he promised, “you’re going to love him.”

* * *

The exhaustive process of refining the Josh Allen Experience took more than three full seasons, with the QB retreating in the down months to Southern California, where he trained under Palmer, the longtime NFL backup turned mentor of prospects. There, a crew of sorts formed, with three signal-callers from the ’18 draft class—Allen, Darnold and Kyle Allen (no relation, now of the Washington Football Team)—and their sensei, perfecting their shared craft on the beach.

Even on television, Allen’s immense gifts leap off the screen. Not many humans are 6' 5", 240 pounds and move like he does. Few can chuck footballs almost the full length of the field, while lumbering over smaller defenders or choosing to out-run them.

As a player and coach, Palmer believes he has witnessed up close some of the most atomic arms in modern pro football, from Mahomes to Matthew Stafford to Jay Cutler; even his older brother, Carson. But Allen, he says, “has the strongest arm I’ve ever seen. When he throws in a group of [NFL] starters, at some point, they’ll all giggle after he bombs one.”

He points out, too, that Allen works with the same trainer as Texans QB Deshaun Watson, athletic marvel that he is, and Allen logs comparable times in drills that measure athleticism and explosiveness. So Allen slings missiles like Mahomes, moves like Watson and stacks up well, in size, against Cam Newton—all of which makes for a supreme talent. But not necessarily a polished one. To Palmer, potential looked like opportunity wrapped inside too many mechanical flaws and ill-advised laterals.

“This is the coolest ball of clay I’ve ever seen,” he told friends. He didn’t want to slow the Experience; didn’t think Allen needed a total makeover. He wanted to emphasize what existed and create comfort within chaos, making Allen max effective and max efficient.

Because Palmer, ultimately, works with his QBs in short chunks of time, he concentrates on one particular facet of each passer’s game every offseason. To begin unlocking the infinite possibilities, in their first spring together, Palmer lasered in on how calculated and consistent movement could improve Allen’s accuracy from his base.

“Remember, he was a bust and inaccurate and he couldn’t hit anything,” Palmer says. “But I realized: This wasn’t one of those big-armed guys with a wild fastball. None of his accuracy issues had to do with his arm.”

On tape, Allen rarely threw with his feet in the same position, which led to a disconnect between his body’s upper and lower halves. At Wyoming, he tended to bounce on his toes, with his feet too close together, making it hard to stride consistently. Palmer forced Allen to shuffle around the hardwood floors at his beach house, wearing socks, until he could steady himself for off-balance throws. Pause the camera, Palmer says, and Allen’s upper half began to look the same, every time he threw.

In offseason No. 2, after a rookie campaign that only exacerbated the doubts coming from analysts and opponents—12 games, 12 interceptions, 52.8% completions—Palmer built on that base. He focused that summer on Allen’s anticipation throws, heading to Doheny State Beach and taking over a grassy area lined with palm trees. Palmer would shout instructions for where Allen was to place his throws, calibrating his touch and angle so the ball arrives when the receiver does: Throw one tree ahead of wideouts, then two trees, then three. Then they did the same drills on the beach, in shifting sand. Palmer compares these workouts to baseball bat swings with a weighted donut: Take the donut off and it feels easier. With his donut gone, Allen’s completion percentage jumped six points in Year 2.

In the lead-up to Year 3, Allen benefited from the upheaval of 2020, using his extra time during the pandemic to buy a house in Dana Point, Calif., near Palmer, and train more than ever before. He called Tony Romo and asked the old Cowboys QB for guidance on his throwing motion. He studied film of Aaron Rodgers, a quarterback he calls “one of the most talented guys to ever play the position, if not the most talented.”

He practiced little hops to open up throwing lanes, hoisting passes midair and experimenting with different arm angles. He worked on his deep ball, “to put it all together, be more consistent.”

The point was to keep the feel and the electricity and the possibility inherent in the Experience, but eliminate—O.K., cut down—the worst parts.

* * *

Allen understands the Experience can be stressful. That it whipsaws the frayed emotional state of Bills fans thirsty for long-ago success. That it puzzles everyone from the anonymous scouts who deemed him atypical to the star cornerback (Jalen Ramey) who called him “trash” in a GQ interview, to the game-charting services, like Pro Football Focus, which described Allen’s torrent start to 2020 not as excellent but as an anomaly. Direct insults, backhanded compliments, Allen pauses, then politely responds. The Josh Allen Experience? In a word? “Unpredictable,” he says.

“I don’t mean that in a bad sense. But any play could have me throwing deep or checking down or running or trying to stiff-arm dudes or jumping over Anthony Barr. I play with confidence and swagger and, when I’m on the field, there’s nothing that I can’t do.” Nothing encompassing vast positive and negative outcomes. It’s just that, now, the scales have tipped.

The latest touches were painted this spring, when Allen summoned offensive players to South Florida for training (in a way that seems less responsible now than then). They were already Experience converts, the tackle Dawkins says, zealots who knew Allen as their leader and the region’s most-famous man child and the tall, stilted white dude unafraid to Nae Nae or Dougie in the locker room. Between workouts, whenever the dad jokes halted, the Bills often turned to each other, unsure if the confidence they felt was shared. Dawkins constantly caught himself saying, “The talent we need is here.”

Well, it had taken Beane three summers, like Allen, to make good on his own promises. Like tailoring his offensive roster around the chaotic energy of his QB, who requires a suitable habitat never seen before in pro football to thrive—from the weather to the cocoon of coaches to the strangest of skill sets. Some of Allen’s past struggles, Beane blamed on himself. He knew that Allen would play “with five guys I plucked from the nearest grocery store,” but that didn’t mean the GM had to take him literally.

Before 2019, he added speedster John Brown and shifty slot wideout Cole Beasley. With better options, naturally, Allen improved in most statistical categories. His touchdowns went up, his turnovers went down, and he led four fourth-quarter comebacks and five game-winning drives. After the Bills lost an overtime playoff game to Houston last January, when the quarterback sat down with his GM and his coaches for an exit interview, he rattled off all the critiques they planned to give him. He already knew the next steps.

Beane kept building around his quarterback. Even though Minnesota had already waved away his previous attempts to trade for Stefon Diggs, Beane tried again this summer, knowing the Experience could use a versatile, No. 1 wideout who doubled as a deep-ball specialist, meaning Diggs could continue to dash open while Allen’s unpredictable dashes unfolded. Per PFF, Diggs had led all receivers in gains on targets of more than 20 yards (635). Beane dealt for him last spring. Even after the influx of supporting talent, the “big question” pundits had about Buffalo remained the same: Allen, always.

And yet, over the first two months of the season, his biggest perceived weakness—downfield accuracy—was a strength. Through Week 9 Allen was completing 53.8% of throws that travel 15 or more yards through the air, seventh-best among NFL starters, compared to 31.9% on such throws over his first two seasons. In Sunday’s matchup with Russell Wilson he outclassed the presumptive MVP front-runner. Attacking the blitz-happy Seahawks with a pass-heavy spread approach, Allen went 31-for-38 for 415 yards, 3 passing touchdowns, a rushing TD and hung 44 points on Seattle while Wilson was the one floundering through turnovers (four) and erratic accuracy.

As the stats, the points and the wins accumulated, the latter coming not in spite of Allen but because of him, social media started circulating a Josh Allen Apology Form. There were boxes to check (I don’t know football . . . Mercury was in retrograde . . . didn’t watch the actual games) along with a suggestion that any gushing praise moving forward should equal any previous disrespect.

* * *

It’s no secret that the makeup of NFL quarterbacks is changing, that the more prototypical, drop-back legends who have dominated football for so long it seems like they’ll never retire will soon be playing a lot of golf. The game is shifting, rapidly, weekly, innovatively, with quarterbacks of different ages and different races and varied sizes and skill sets. The only thing they seem to have in common is how little they seem to have in common. And no player in the modern NFL typifies just how adaptable and malleable and creative the position has become than Allen, who stands alone, apart, in a way.

That’s not to say he is the best quarterback in the NFL, or the fastest, or the strongest, or the tallest, or the most refined. Allen is so many things crammed into one funky package that he—and the Experience—are impossible to clearly define. He’s big and fast but runs clunky. He can chuck the ball but not with a poetic grace. Palmer makes the argument that Allen is the most talented athlete to ever play the position, because he can move and throw like that at 6' 5".

Palmer says to picture this: Allen, one day soon, under center, Diggs set wide to the left. Diggs runs a curl at the 14-yard-line, while the protection breaks down. Allen scampers right, away from impending doom, maybe slips a tackle or five. Diggs spies his QB on the move, same as always, and he bolts downfield on a post route. Allen whips the ball across his body, 75 yards down field, all the way to the end zone, where Diggs settles underneath for an easy score. That play, Palmer promises, is coming—one indicative of a new, exhilarating landscape in pro football.

“The future of the game is the quarterback’s ability to create time and space,” Palmer says. “Josh Rosen—and this has nothing to do with what happened to him, because he’s been a victim of situations—but I do think [he] is the last quarterback who will ever be taken high in the draft whose main attribute is not movement.”

Which is funny, right? That the quarterback deemed too atypical for some teams before the draft two years ago now has Bills fans dreaming of the most unlikely thing of all: their first, Su … pe … r … well, let’s not jinx it.

* * *

In the most important ways, Allen is just like the city that adopted him. On this, everyone seems to agree. Bills offensive coordinator Brian Daboll, a Western New York native and a long-suffering Bills fan himself, may not approve of how strangers describe Buffalo, a city that so few of them have ever visited. But he’s still aware. He says his unit is emblematic of all the usual clichés used to describe places that are less than desirable to outsiders: tough and hard-nosed and working class and all that. Among his starters, he counts just one first-round draft pick. The one whom most of the football world doubted.

So Beane can say that nobody sees Buffalo as a destination, and that’s largely true. Allen can counter that he loves his adopted city and hopes he never leaves, and that’s also true. But it’s Daboll who espouses the most relevant sentiment for those lunatics swilling LaBatts and jumping through tables in the parking lot. The Experience? It’s theirs. Finally.

“This dude is so Buffalo,” Daboll says.

Beane believes the outsiders remain less-than convinced. That they eye the Josh Allen Experience with skepticism, enjoying the thrill and checking the apology forms, but still expecting Allen to make the kinds of mistakes that once defined him, like the two picks he threw against the Titans on a Tuesday night in Week 5, or his struggles through the wind and rain against Mahomes’s Chiefs six nights later. But not in Buffalo. In Buffalo, they’re all-in. In the same city where Beane twice had to switch barbers due to incessant needling about his roster-building, he can sense something unfamiliar wafting through the air. It’s not wing smoke; it’s … optimism.

In his first season as GM, Beane helped guide Buffalo back into the playoffs, ending the drought. He saw fans crying in the stands. He saved some of the videos, for whenever he needs the inspiration. But now, it’s different. For the first time in forever, the Bills are a legitimate contender that Beane molded around Allen much like everyone around Allen molded his unformed clay into a true franchise quarterback. The refinement of both roster and quarterback has led right here, to the overflowing bandwagon and the promising, if not perfect, start.

Thomas, one of many Hall of Fame Bills, sees what’s possible, and he hasn’t seen that for a long, long time. He did Zoom calls this summer with the current players and former greats, luminaries like Bruce Smith and Steve Tasker and Fred Jackson. He believed the players knew where they might be headed; he did not believe they could understand what a championship would mean. “Guys,” Thomas told them, “if you win one Super Bowl, you’ll be the greatest team in Bills history.”

He didn’t have to say the rest, didn’t need to remind them he’d lost four straight. “We have the guy that nobody wanted,” he says. “People said bad things about him like they say bad things about Buffalo in the winter.” But, he told the players, “If you win, we win. I’m gonna feel like I won it, too.”

Allen hopes he can deliver that, for himself and for his coaches and for Thomas and for the believers in Bills Mafia. He likes this team, in this season, and he sees now the infinite possibilities.

So just when does the Josh Allen Experience end? “Hopefully,” he says, “the second week of February.”

0 Comments