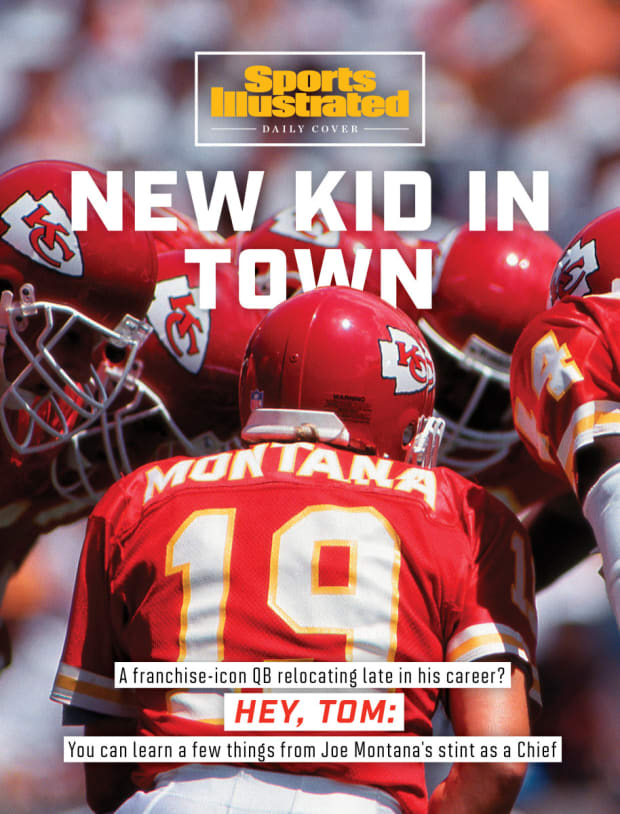

There’s a blueprint for an iconic quarterback moving on to a new franchise: Joe Cool’s two-season stint in Kansas City.

Joe Montana’s legacy in Kansas City began with a rancid smell wafting through the offensive meeting room.

It brought to mind rotten eggs, or, less diplomatically, a fart, cruel and penetrating enough to stand out amid a group of sweaty grown men enduring merciless two-a-days in the Missouri heat. It was so putrid and unrelenting that the meeting, the unit’s first, was called off and the room was evacuated.

Landing Montana in a trade was a big deal for the Chiefs, who, despite their success in the years leading up to his arrival, starved for more consistency at the quarterback position. In his new home, Montana was not the oft-injured statue who was replaced by Steve Young in San Francisco. He was Hendrix at Monterey.

During the breathless coverage of Montana’s recruitment the previous spring, a Kansas City radio station would accompany any news with the song “Lawyers, Guns and Money” by Warren Zevon, with the clear message being: Utilize all three, if necessary, to get him here.

As they left the room, players began to wonder who was responsible for releasing the stench—who had dared to cross Marty Schottenheimer before his big monologue. The coach did not tolerate nonsense and was already on edge, having spent the offseason luring Montana away from the 49ers (and the Cardinals, who had offered Montana

$5 million more). Breaking open a tube of ammonium hydrosulfide, better known as a stink bomb, seemed like a death wish.

Slowly Montana, 37, a four-time Super Bowl champion, seven-time Pro Bowler and two-time Most Valuable Player, emerged as the primary suspect. And so began two years of epic pranks, decadent meals and undeniable cool: the perfect blueprint for a GOAT switching franchises.

“People were walking on eggshells at this meeting because it’s Joe Montana,” says Danan Hughes, a rookie wide receiver at the time. “But everyone said it was Joe that did it, as an icebreaker. He wanted people to know he was one of the guys, and that he was nothing special.”

Twenty-seven years later, Tom Brady agreed to terms with the Buccaneers, embarking on a similar journey from a dynasty he helped create to a town starving for football relevance and celebrity power. No longer under the thumb of Bill Belichick, Brady has already carved out a presence in Florida that has ranged from swaggering (bursting into a random person’s home because he thought it belonged to his new offensive coordinator) to openly defiant and, by some measures of public health, irresponsible (disobeying local coronavirus ordinances by holding workouts in public parks). But ask guys who played with Montana back in 1993 and ’94 and they’ll tell you the heaviest lift is yet to come.

Teammates and coaches remember Montana as a man at ease with his place in life; someone who could glide around an unfamiliar locker room and instantly win over his new teammates. Montana made the social aspect of his job look as effortless as the physical, which those around him insisted was just as important.

During his introductory conference call in Tampa a few weeks back, Brady was asked about Montana’s journey and what he took away from it, having grown up idolizing the quarterback. During his response, stuck in the middle of an elongated platitude about keeping one’s body in shape and working hard, was perhaps the most painfully honest thing Brady has said since moving on from New England.

“Life continues to change for all of us,” he said.

That is true. But what if that change requires you to revert to the man you were 20 years ago?

***

Those who knew the young Tom Brady remember someone who would eagerly bring Dunkin’ Donuts into the facility for early-morning meetings (these were the days before his breakfasts required tempeh or avocado mousse) and dote on the defensive coordinators looking for a quarterback to simulate Sunday’s opponent. Back then, he seemed to possess the emotional intelligence required to advance in one of the NFL’s few meritocracies. He was personable and gracious, someone who would bump into the recently signed emergency long snapper in the bathroom and already know something about him. Later, by all appearances, he was smart enough to realize that keeping up the image of the eager, wide-eyed rookie with everything to prove was good for business.

For years, Belichick treated one of the most famous humans on earth as the complete opposite, underpinning the entire Patriots ethos: that no one person was more important than any other.

By the time he had become an established star, Brady stopped going to Outlaw biker bar with the rest of the offensive linemen, but he made every small barbecue. He compiled elaborate, night-before game cut-up videos that were essentially a brain dump of all his weekly notes to share with the rest of the class, something former teammates say they have never witnessed anywhere else.

He had an internal list of how best to treat his teammates. A Randy Moss mistake was addressed in private, off the field, in a quiet moment between their adjacent lockers. A Wes Welker mistake, on the other hand, could be loudly and publicly raised, as if one were training a Labrador retriever.

“You have to be a part of the group, but also above the group,” says Matt Cassel, a New England teammate of Brady’s for four seasons. “When we did manage to go out together he was just one of the guys. Having laughs. He has a great personality. You can joke with him. He’s a normal guy.”

Still, Brady spent the better part of two decades with the Patriots sublimating his swagger to preserve his team’s identity. Montana, on the other hand, was Joe Cool, the guy who authored moments such as the Catch and the Chicken Soup Game.

Despite all that Brady had sacrificed for the team—including millions over the years to help with the salary cap—Montana had an easier departure, given that he had missed virtually all of the previous two years with an elbow injury and Young had just led the Niners to a 14–2 season. “Unlike Tom, Joe felt like it was time to leave,” says Paul Hackett, Montana’s offensive coordinator in Kansas City. “Joe had been replaced. There wasn’t a question about whether or not it was time to leave.”

On the Tuesday night he arrived in Kansas City, he asked his new center, Tim Grunhard, to grab a beer at a spot called Kelly’s. The place was empty. These were the days before cellphones and social media geotags. Within a half hour, Grunhard remembered, the place turned into “St. Patrick’s Day,” with Montana graciously mobbed, at home and in love with his new lot in life.

Stink bombs aside, Montana did not barrel into his new locker room in Kansas City, but integrated himself slowly through a series of small gestures. Grunhard said that Montana was the first and only quarterback he saw to take the blame for a botched QB-center exchange. Montana would spend the week after wins taking his teammates out to dinner, position group by position group, to thank them for keeping him upright.

During a game plan installation early in the season, Schottenheimer stopped a meeting when the team arrived at short-yardage and goal-line situations and took the team out on the field to practice live. The offensive staff was dialed in, frantically lining up the first play when everyone realized that the quarterback was nowhere to be found.

Montana had somehow managed to slide out of the belly of Arrowhead Stadium, climbing up the steps armed with a water balloon cannon and a stockpile of ammunition. “You have to do things like that,” Hackett says. “I’ll bet that, heading into that practice, I was taking things too seriously. And then, one of the first people he hit with a balloon was me. So how am I going to react?

“That was part of Joe’s magic. Real magic.”

Sacks were his fault. So were interceptions and drops. Offensive linemen felt like his kids, far more wary of disappointing dad than getting screamed at. They developed a way to check on each other on Mondays after games. One member of the crew would sheepishly ask the quarterback whether, after meetings, he’d be able to go out and play a round of golf. A yes would indicate that the protection was satisfactory the day before. A no would be the nicest possible way Montana could say “get your s--- together.”

Once a comfort level was established, Montana was able to solidify his hold on the locker room by acting as the player representative during Schottenheimer’s most tyrannical moments. The interplay between Montana and Schottenheimer was something of a ballet, with the coach knowing he needed to cede some power to the quarterback and Montana knowing he needed to advocate for his teammates without overstepping any boundaries.

Martin Bayless, the team’s defensive MVP in 1993, remembers a particularly wicked stretch of 16 consecutive days of full contact two-a-days that left the roster battered and mentally worn down. On the eve of Day 17, as a player mutiny began to develop, Montana told them he would take care of it.

In front of the full-team meeting later that day, he stood up and said: “Hey, Marty, these guys have been working pretty hard. How about a day off?”

Schottenheimer smiled and said: “I recruited you already, so sit down. We’re practicing twice.”

On Day 18, Schottenheimer gave the team their first vacation day.

***

They all looked over as he sauntered into the huddle, Monday night, Week 7 against John Elway and the Broncos. It was his second season in Kansas City; in his first, Montana had taken the Chiefs to an 11–5 record and within a game of the Super Bowl. Now, they were down by four points late in the fourth quarter and had the ball at their own 25-yard line. In the huddle before calling a pass play to Marcus Allen, Montana looked at his teammates, smiled and said: “Hey, any of you check out the chaps on those cheerleaders?”

This was a recycled Montana bit, of course, but, man, did it feel cool to hear it live. He’d famously asked his 49ers teammates whether they noticed actor John Candy in the stands before embarking on a 92-yard game-winning drive in Super Bowl XXIII. Juxtaposing the outward chaos with an almost equally maniacal sense of calm did not get old. This was football mindfulness at its peak. He did it because it worked.

But against Denver, he kept going.

“Listen, guys, this is what I do,” he said, like a plumber approaching a clogged sink. “Relax, give me some time, and we’re going to win.”

“We knew, at that point, we were going to win that football game,” Grunhard said. “Joe really and truly believed that. So we did too.”

Montana went 6 of 7 on the ensuing TD drive, throwing for all but 10 of the team’s yards. Not bad for a man whose elbow had routinely blossomed to the size of a palmable children’s basketball. Whose back ached. Whose knees hurt. Who had no earthly reason to be here other than the love of the performance. The devotion to the bit.

Nine months earlier, he’d walked into the locker room at halftime of a playoff matchup with the Houston Oilers in which the Chiefs trailed 10–0. Buddy Ryan’s defense had been landing one haymaker blitz after another. The room was silent. Montana had just whipped an incomplete pass off Willie Davis’s fingertips at the end of the quarter and was ecstatic about it. Something felt right. He told everyone that he had it all figured out. Everything was going to be fine. And the Chiefs scored 28 second-half points to win by a touchdown.

At another practice, during his first weeks with the team, the secondary had acquired intel on the plays the offense would run during a red zone practice and were prepared to eat Montana alive, jumping on all his primary reads and gobbling interceptions. A few minutes later, they headed to the sidelines on water break totally dejected. Despite his new teammates knowing what would happen, Montana went a perfect 9 of 9.

Moments like that were common in Montana’s two years in Kansas City, when he led the team to a pair of playoff berths before retiring for good. The pressing question when any legend moves from one place to another is How much of the magic was his own and how much belonged to the team? This is the lunacy of insisting on proving it all again, the reason we find so many more of our legends out decompressing in a vineyard somewhere. Who would feel the need to do it all over? Who would lay themselves this bare?

With the glow of secure retirement in the near distance, Montana did, pushing through the minutiae of a new system and a new routine, making new friends with 300-pound linemen when high rollers at golf courses all over the country would have forked over five figures just to kiss his rings for 18 holes. It worked for Montana because he made those connections; it also helped that his play answered that pressing question.

“Once he got on the field, he was Joe,” Bayless says. “He was magic.”

Read more of SI's Daily Covers stories here

0 Comments